The Billable Hour and How It’s Harmful

The billable hour is preventing growth in the legal industry.

In general, the billable hour is a way to measure the value of the services provided to a client or customer—based on the amount of time it takes a professional to complete the service. You probably can understand all that from the term itself.

What I really want to discuss are the unintended consequences of using the billable hour carelessly. These consequences are significant, especially when the billable hour is used as a performance metric in large organizations.

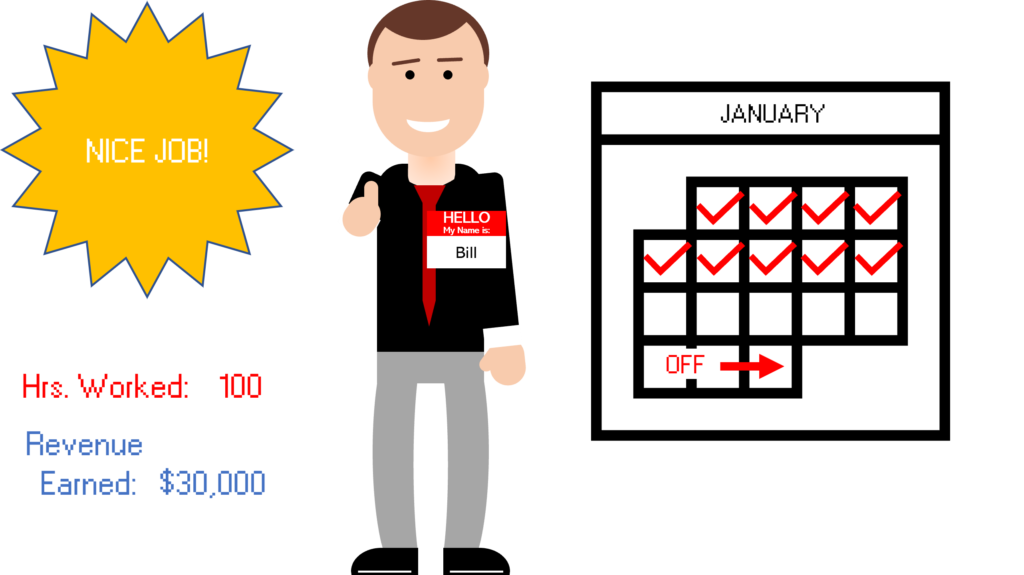

An Example: Bill:

Here’s what I mean. Assume Bill is a mid-level lawyer in a large firm. Bill knows that his performance review is based almost exclusively on billable hours—and he needs to bill 170 hours every month to keep his job.

On January 1, Bill is assigned the task of drafting 20 employment contracts. It takes him 5 hours to draft each contract—and over the next two weeks, drafts these 20 contracts. This is great for Bill, because he just racked up 100 billable hours that count toward his performance metrics, and earned the firm $30,000. Now, Bill only has to work 70 more hours to meet his January performance metrics.

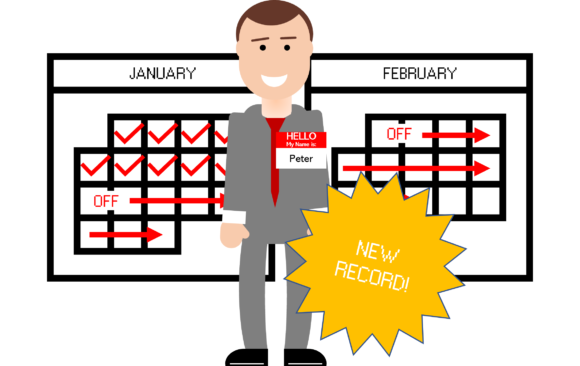

An Example: Peter:

Peter, on the other hand, works for a different firm. Unlike Bill, Peter’s performance review evaluates the amount of work he produces—and he needs to earn 170 performance points every month to keep his job. He gets 5 points for every employment contract he drafts. On January 1, Peter is assigned to 20 employment contracts.

Peter knows that there is a software program he can use to help him draft the contracts. He expects the program will significantly decrease his drafting time without sacrificing quality. And since he earns 5 points for each contract, he decides to try the program to see if he can save himself some time. Peter spends part of the week learning the software program and modifying it as needed. Then uses the program to draft the 20 contracts. He’s done drafting all 20 contracts in 40 hours.

Later in the week, Peter gets assigned an additional 40 contracts. So, he uses the rest of the week, and all of the next week to draft these contracts. At the end of the second week, Peter has drafted a total of 60 contracts, earned 300 performance points (enough to carry him through mid-February) and earned the firm $90,000. Then he takes a vacation, because he’s earned it.

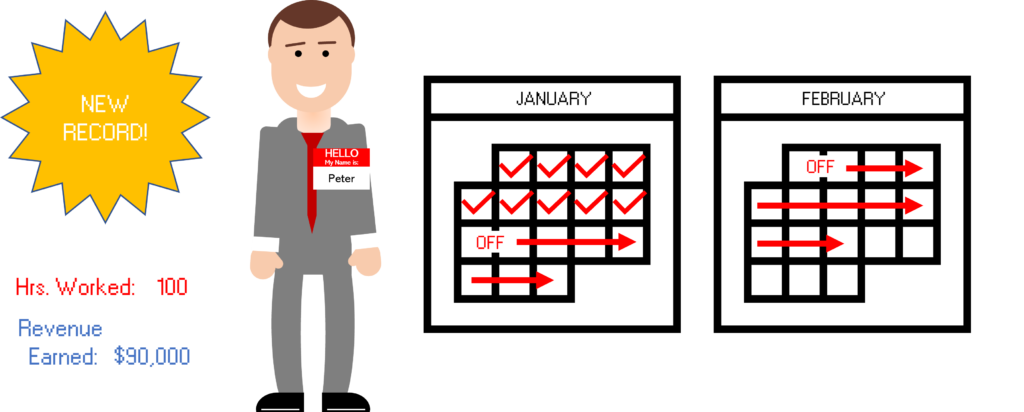

Comparison:

In 100 hours:

Billable hour Bill drafted 20 contracts for $30,000 of revenue.

Performance Pete drafted 60 contracts for $90,000 of revenue, and is able to take a long vacation.

This difference is due entirely to the billable hour. Both lawyers produced the same quality of work, at the same price for each client. But their methods were different because their incentives are different.

The Breakdown:

Bill’s incentive is to spend time working. So, that’s what he does. And if there’s a way to spend less time working—it doesn’t really matter to Bill, because he is required to work 2,000 hours every year.

On the other hand, Peter’s incentive is to earn points by completing projects. So, he’s encouraged to find the best ways to work. If he finds a better way, he can produce more work, for more clients, earn more revenue, and take a well-deserved vacation.

So, while Bill’s toiling away on January 15 to meet his billable hour requirement, Peter is sipping Mai Tais on a Hawaiian vacation.

The Result:

Now, numerous professions use a version of the “billable hour,” and it’s not all bad. Car mechanics usually call it “labor,” business consultants, accountants, and lawyers call it the “billable hour.” And it can be a useful, and sometimes the only way, to value a service. So, I’m not taking the position here that the billable hour should be eliminated entirely. My opinion, is that the billable hour is often used as a crutch, and applied inappropriately for a few reasons.

- Employers don’t fully understand the negative consequences of using time as a performance metric. So, I created this blog (and a web application, Accelerator Lex) to share my opinion and hopefully get the message out. If you’re a lawyer and think that legal technology is inapplicable to you—I’d encourage you to reevaluate. The software program I elude to in the story is over 20 years old, and it’s still unused by many firms.

- Legal services are difficult to value (because they’re nuanced and complicated, and rife with uncertainty and risk), and law firms haven’t found something better than the billable hour. And that’s why I created a fee calculator called Accelerator Lex. So, if you’re a lawyer—go check that out—you might find it useful to determine fixed fees or restructure your firm’s performance metrics.

- There’s a large knowledge gap between lawyer and client. So, clients don’t know if they’re paying the right amount. And that’s why I created GavelBook—it’s like the TrueCar or Zillow for legal services. If you’re about to hire an attorney, check it out—it might help you understand whether you’re about to hire the right lawyer for you.

Unlock your abilities with our fundamental guide to mastering successful time management and boosting overall productivity now.

there

there